The option several members of the UK Hoverflies Facebook group have adopted is to collect specimens and store them for the autumn when they send them to me for identification. I have written about this before, but it is always worth an update.

Killing specimens

There are several ways of doing this:

The simplest is to pop the container with your fly in it in the freezer for 24 hours - very few summer insects will survive such a time in the freezer.

An alternative is to use ethyl acetate or nail varnish remover - couple of drops on a piece of tissue popped into the container (beware that Ethyl Acetate is a solvent of some plastics, especially polystyrene which is often used. So, if in doubt use a small glass tube.

A further alternative is to take the fresh early growth from cherry laurel and crush it up into small fragments before putting as a deep layer in a tube or bottle and covering it with a wad of tissue paper - tightly pressed down. This is the traditional entomologists' 'killing bottle' and makes use of the cyanide released from these young leaves. I use this system for bigger flies, sawflies and other Hymenoptera (and any other big insects that are otherwise difficult to kill quickly).

Storing specimens

In an earlier post I showed how John Bridges does this using little plastic envelopes. It is a great system but he and I did hit a bit of a problem with mould, so I think that the alternative is to use a breathable envelope - I have previously shown how to make these too but here is the sequence again:

|

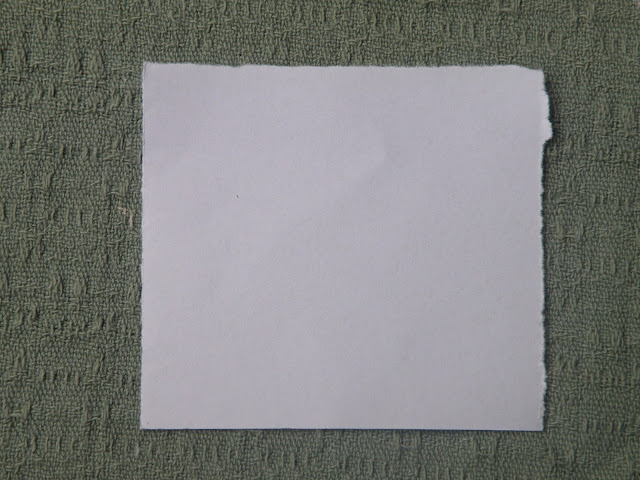

| Stage 1. cut a piece of paper about 7cm square |

|

| Stage 2. Turn one side over to form a triangle |

|

| Stage 3. Turn over one side to seal the edge - it is often a good idea to stick this down with a slip of masking tape. |

|

| Stage 6. turn over the open end and again seal with masking tape. |

Postage

I once sent an envelope of fungus gnats to Peter Chandler in a poorly protected package - he later wrote to say that they had arrived in many tiny pieces but he had managed to construct a list from the genital capsules of some of them! That was an object lesson for me, so I now send my samples in plastic boxes - the sort you get from a takeaway Chinese meal.

No comments:

Post a Comment